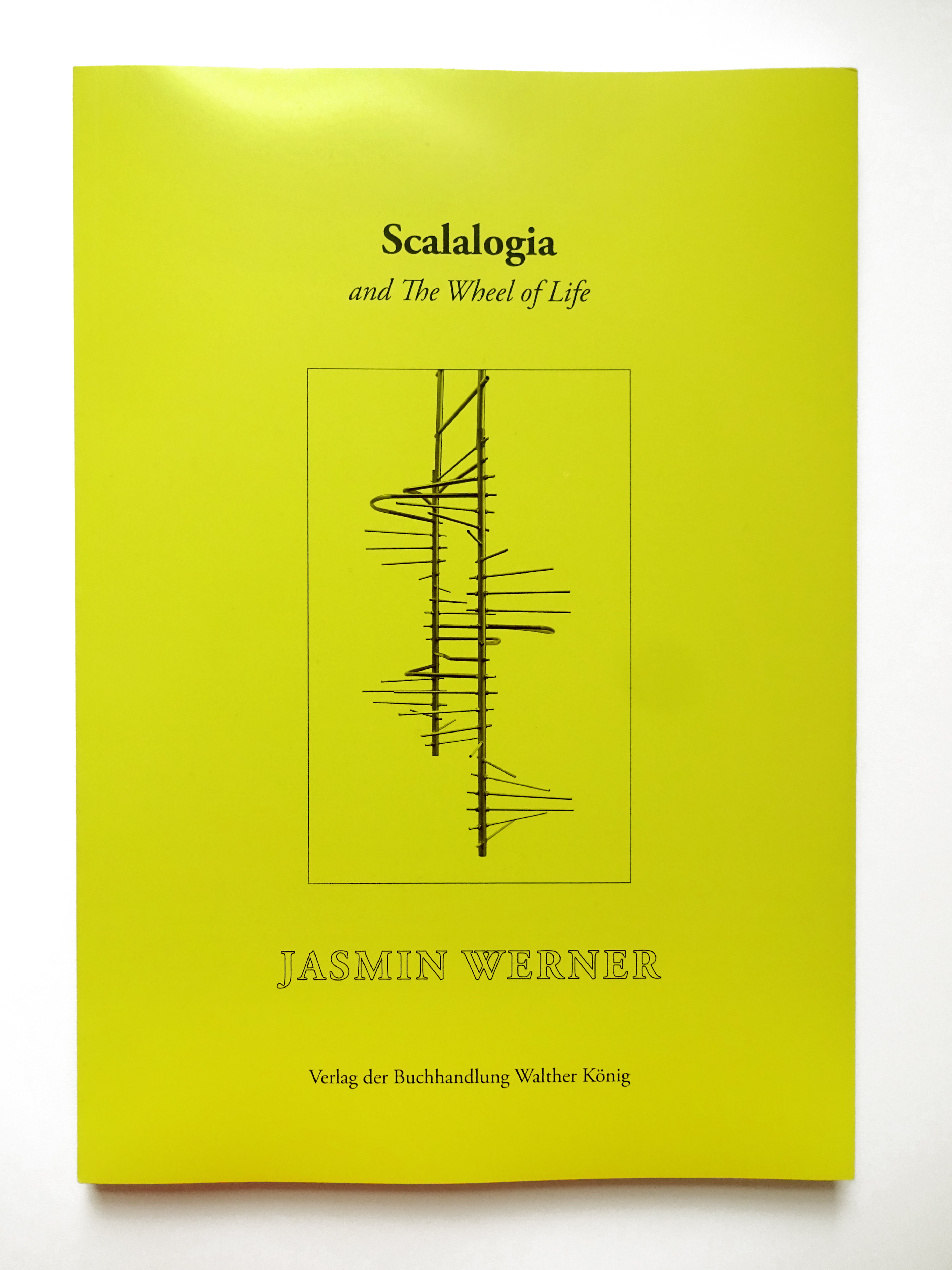

Rarely does an artwork respond to political conditions as conciselyas Jasmin Werner’s Send Money Fast (2023), on the facade of KWInstitute for Contemporary Art. It involves prefabricated cassetteroller shutters installed on the ground-floor and first-floor windowsof this well-known art institution, with the logos of Ria, Small World,and Western Union emblazoned on the painted shutters. Thesecompanies offer money transfer services or remittances, commonlyreferred to as payments, that can be made by migrants to familymembers and acquaintances in their home countries. While the GermanBundestag debates how to reduce the “attractiveness of ourwelfare state [Sozialstaat]” to accommodate fewer asylum seekersin the future, the finance minister suggests blocking remittances tocountries of origin. Werner, who lives and works in Berlin, criticallyengages with the architectures of power, focusing on the often-invisiblestructures that keep the gears of our capitalist world spinning.With Send Money Fast, she directs her gaze towards financial flowsand indirectly towards migration movements.

On a fourth painted roller shutter, we find the “Admiral”, a butterflybelonging to a migratory species that travels over long distances dueto overpopulation and climate change; these are some of the samecauses responsible for human migration. Additionally, there is the exploitationof resources that inevitably leads to precarious living conditionsfor civilian populations, forcing them to flee from their countries,referred to as Herkunftsländer origin countries in Europe.

In its political relevance, Send Money Fast reminds me of artworkby groups like New York-based Group Material, which used advertisingspaces for some of their works and exhibitions, placing artworks(as advertisements) in newspapers or on billboards while actively engagingwith people in their neighborhood. They connected art withpolitical activism. I also think of the work of Belgian artist GuillaumeBijl, who, since the 1970s, has transported the interiors of establishments—like driving schools, supermarkets, bedding stores, or waitingrooms—from public spaces into art institutions and galleries, thus deliberatelyquestioning the relationship between art and capitalism.

Werner’s work is a critically ironic exploration of a digital financialinfrastructure that we see daily, in large cities especially, and that iscrucial for only a portion of the population yet vital for the survival ofthose who rely upon it. After all, it involves billions flowing through remittancesto family members, making those payments existentially important.Werner collaborated on her installation with Berlin sign painter,Dawid Celek. Celek, who offers his services as a painter and graffitiartist for various businesses and individuals on eBay, hand-painted aseries of roller shutters of mobile phone shops in Moabit, where theartist resides. Celek is originally from Poland and employs several Polishworkers in his painting business for projects in Berlin, Germany,and Poland itself (which is one of the largest corridors for remittances).

Furthermore, Send Money Fast encourages us to consider financialflows beyond the realm of art. In a hyperconnected, globalized world,the butterfly effect can often be observed where local events haveglobal repercussions. The thesis of British professor Ian Goldin, whoteaches at the University of Oxford and co-authored The Butterfly Defect(2014) with Mike Mariathasan, delves into the growing gap betweensystemic risks and their effective management. He demonstrates howthe new dynamics of turbocharged globalization have the potentialand power to destabilize our societies. To prevent this process in thelong term, we need more solidarity. As Goldin asserts, if individualswant to win, we all must win.

Text by Fabian Schöneich